It's been a few years now, but back in 2016 I visited the Adler Planetarium with my sister on our visit to Chicago and I took some geological themed photos of the exhibits and building at the Adler Planetarium. So here, along with a few other upcoming posts, is a geology of Chicago through pictures.

|

| View of the Adler Planetarium from the front. |

The building is a 12-sided dodecagon and opened in 1930. The planetarium is located on the waterfront of Lake Michigan and has a lovely series of geological exhibits and is, in and of itself, a lovely geological centerpiece.

|

| The building is lined with very nice gneiss slabs. |

Twelve bronze plaques adorn each of the twelve outside corners of the building. The plaques are a a stylized depiction of each zodiac sign, which were sculpted by Alfonso Iannelli, casted in bronze, and then surfaced in 22-karat gold.

|

| All tasks for geologists. Although I hear they limit the amount of people allowed to lick the meteorite (pre COVID of course). |

Clearly this planetarium was made for geologists.

|

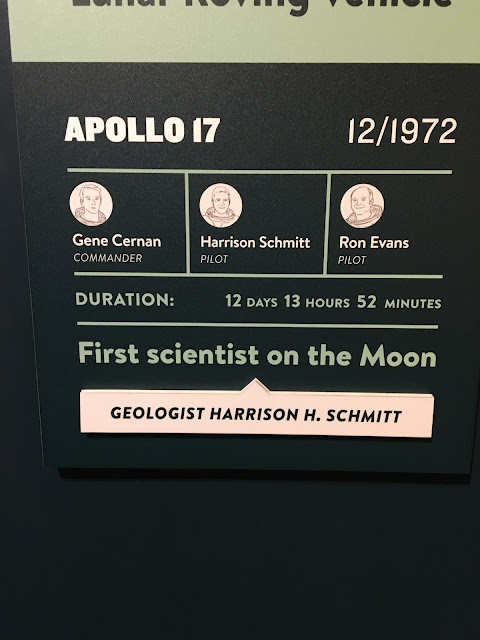

| The first geologist on the moon, Harrison Schmitt. |

In total, there has been 12 people who have stepped foot on the moon (as of today). And while a few of the previous Apollo missions collected rocks or studied moonquakes, it was determined that in order to obtain the "right" rocks, that a geologist would need to be trained as an astronaut as opposed to training an astronaut as a geologist. The final mission that had people walk on the moon was Apollo 17 that carried Harrison Schmitt to the moon, marking him as one of the last 2 people to set foot on the moon.

Harrison Schmitt received a Bachelor of Science from the California Institute of Technology in 1957 and a Doctorate in Geology from Harvard University in 1964. Following his graduation he worked for the Norwegian Geological Survey in Norway, the U.S. Geological Survey in New Mexico and Montana, and taught courses on ore deposits at Harvard as a teaching fellow. Following this he worked with the U.S. Geological Survey's Astrogeology Center where he was project chief for the lunar field geological methods and participated in photo and telescopic mapping of the moon. He was also one of the people instructing the NASA astronauts in geology of the moon and how to pick the samples. While on the moon, Schmitt collected rock and soils samples supporting theories of lunar volcanic activity.

|

| Apollo 15 moon rock, a piece of the "Great Scott Rock". |

Prior to Harrison Schmitt traveling up to the moon, some geological samples had been collected by previous astronauts. Here is a piece of one of the rocks collected. This is part of Lunar Sample 15555, also known as "Great Scott", collected on July 30, 191 as part of Apollo 15. The rock sample was the largest rock taken back on Apollo 15 and was found 12 meters north of the rim of Hadley Rille. The rock is a medium grained olivine basalt, dated to 3.3 billion years old and contains olivine and pyroxene phenocrysts. The bulk composition is thought to be that of a primitive volcanic liquid.

|

| Planet and moon buddies |

While we are on the topic of the moon, why not take home a stuffed moon! Unfortunately, since it is not made of cheese, it isn't scientifically accurate. ;-)

|

| An iron meteorite piece that came from the Meteor Crater impact in Arizona. |

Some other geological things within the museum include this piece of iron meteorite from the Meteor Crater (AKA the Barringer Meteorite Crater) in Arizona. The entire meteorite was ~150 feet wide and produced a crater 3/4 of a mile wide and more than 550 feet deep. The impact happened ~50,000 years ago and is likely the best preserved meteorite impact on Earth due to the young age and desert conditions. The impact produced an explosion equal to 10 million tons of TNT.

The meteorite pieces found around the crater are known as the Canyon Diablo Meteorites and are composed of nearly solid nickel-iron with some graphite and diamond inclusions. The source of the meteorite was likely from the asteroid belt, a region of space between Mars and Jupiter. These chunks of rocks in space were formed at the same time as the rest of the planets, however the gravity effects between Jupiter and the sun prevented another rocky planet from consolidating, leaving behind these chunks of iron, nickel, and other rock chunks.

References

|

| Is Pluto a Planet poll |

And the last stop on our geological tour of the Adler Planetarium is the Pluto Poll. "Should Pluto be a Planet"? And this poll right here is what a lot of scientists have a problem with. Science works by taking the data we have and formulating hypothesis and identifying things based on that data. It is not a popularity contest. Science doesn't care what you think of Pluto or whether it should be a planet. Regardless of public opinion it is currently identified as a "dwarf planet" and will stay that way, at least until we have better data to change it. I have talked extensively about Pluto in the past and came up with these Fun Facts.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Due to the large number of spam comment (i.e. pretty much all of them). I have turned off commenting. If you have any constructive comments you would like to make please direct them at my Twitter handle @Jazinator. I apologize for the inconvenience.

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.